This bears closer inspection.

Certain things in life are better shared.

The cargo scooter was probably meant for serious purposes, but when you need a break, it's nice to be able to go helling around the lab. And it's a handy way to get laundry back and forth between the beamline where we work and the closet behind the synchrotron power sources where the cleaning staff wash rags and mops.

The cargo scooter was probably meant for serious purposes, but when you need a break, it's nice to be able to go helling around the lab. And it's a handy way to get laundry back and forth between the beamline where we work and the closet behind the synchrotron power sources where the cleaning staff wash rags and mops.  Going for a scoot and doing the wash are well-suited to filling all those long stretches while you wait for the spectrum to accumluate.

Going for a scoot and doing the wash are well-suited to filling all those long stretches while you wait for the spectrum to accumluate. After a long night, we had the inspiration to melt down a bar of orange chocolate and use up the last of the strawberries. They look very natural, as though they somehow belong among the computers at the beamline desk.

After a long night, we had the inspiration to melt down a bar of orange chocolate and use up the last of the strawberries. They look very natural, as though they somehow belong among the computers at the beamline desk.

Science sidebar It breaks down like this: when we shine our single-color x-ray beam onto a chunk of material, we're especially interested in the x-rays that it emits at lower energy (redder) than we put in. It's called inelastic scatttering because what you put in is different from what comes out, as if you tried playing with a hacky sack the way you would a bouncy red rubber ball; you put in a lot of energy, but the hacky sack would come back with a lot less than you threw it with. Actually, I think I overdid it by picking a hacky sack, but you get the idea. By contrast, a high-bouncing rubber ball would be almost perfectly elastic; after a bounce, it has almost all of the energy it had beforehand. Inelastic x-ray scattering with photons is similar but more interesting because it involves the material's electrons, which are more complicated than walls (in some ways).

Science sidebar It breaks down like this: when we shine our single-color x-ray beam onto a chunk of material, we're especially interested in the x-rays that it emits at lower energy (redder) than we put in. It's called inelastic scatttering because what you put in is different from what comes out, as if you tried playing with a hacky sack the way you would a bouncy red rubber ball; you put in a lot of energy, but the hacky sack would come back with a lot less than you threw it with. Actually, I think I overdid it by picking a hacky sack, but you get the idea. By contrast, a high-bouncing rubber ball would be almost perfectly elastic; after a bounce, it has almost all of the energy it had beforehand. Inelastic x-ray scattering with photons is similar but more interesting because it involves the material's electrons, which are more complicated than walls (in some ways).  So hier goes: At the location of an atom some material, an electron absorbs the energy of the x-ray photon and comes flying out of its comfy little neighborhood into the wide open vacuum the material is parked in. Then any other electrons nearby who have been patiently waiting, stuck at higher energy seats than the one just vacated, can fall down into the hole. They can't just fall to lower energy, though, without getting rid of some energy. Specifically, they have to get rid of the energy difference between their old energy and their comfy new lower energy. (Our universe is fundamentally lazy. Things like to be at low energy, the same way that people like to spend rainy Saturday mornings on the couch with a cup of coffee.) So when that electron relaxes into the hole, that energy has to go somewhere else, and sometimes it's into another x-ray photon, born out of sheer necessity. A lot of the time, this is the red rubber bouncy ball effect, and we get out the same color x-ray we put in. Some of the rest of the time, it's more on the hacky sack side, and we get back light that has less energy than the light that went in. I have friends who will ask, so, yes, sometimes it's possible that you get back a photon with more energy than the one you put in, but that means something in the material gave up energy, and usually if it could do this it already has.

So hier goes: At the location of an atom some material, an electron absorbs the energy of the x-ray photon and comes flying out of its comfy little neighborhood into the wide open vacuum the material is parked in. Then any other electrons nearby who have been patiently waiting, stuck at higher energy seats than the one just vacated, can fall down into the hole. They can't just fall to lower energy, though, without getting rid of some energy. Specifically, they have to get rid of the energy difference between their old energy and their comfy new lower energy. (Our universe is fundamentally lazy. Things like to be at low energy, the same way that people like to spend rainy Saturday mornings on the couch with a cup of coffee.) So when that electron relaxes into the hole, that energy has to go somewhere else, and sometimes it's into another x-ray photon, born out of sheer necessity. A lot of the time, this is the red rubber bouncy ball effect, and we get out the same color x-ray we put in. Some of the rest of the time, it's more on the hacky sack side, and we get back light that has less energy than the light that went in. I have friends who will ask, so, yes, sometimes it's possible that you get back a photon with more energy than the one you put in, but that means something in the material gave up energy, and usually if it could do this it already has.  The point is that we expect that the only x-rays the material can emit must come from electrons in the material relaxing down into a hole. They can't have more energy than they get from the most energetic electrons lose when relaxing into the lowest energy hole.

The point is that we expect that the only x-rays the material can emit must come from electrons in the material relaxing down into a hole. They can't have more energy than they get from the most energetic electrons lose when relaxing into the lowest energy hole.  So it was with a depressing sensation of having misused our time (and of having failed to think the matter through) that we laid plans to make use of the next day, left Brian to his day shift, and trudged against the commuters to the guest house. You can see now why we needed the chocolate-covered strawberries.

So it was with a depressing sensation of having misused our time (and of having failed to think the matter through) that we laid plans to make use of the next day, left Brian to his day shift, and trudged against the commuters to the guest house. You can see now why we needed the chocolate-covered strawberries. I woke up to another rainy Swedish late afternoon--a terrible time to wake up. Our usual activities in the lab don't involve as much exercise as I'm used to getting, but my dorm room made a nice place to do a few pushups and situps before heading back.

I woke up to another rainy Swedish late afternoon--a terrible time to wake up. Our usual activities in the lab don't involve as much exercise as I'm used to getting, but my dorm room made a nice place to do a few pushups and situps before heading back.  Walking out in the balmy weather, I wasn't nearly as prepared for the rain as this local. Unless this was another American who was on his way to the pool.

Walking out in the balmy weather, I wasn't nearly as prepared for the rain as this local. Unless this was another American who was on his way to the pool. On the way to work I stopped by the ICA for a few necessities. A typical receipt might look like this one, including such commonplace Swedish necessities as glass cookies and Giant Cactus. I think "moms" means "tax"--especially since my mom used to playfully exact food tax in the form of a bit of

On the way to work I stopped by the ICA for a few necessities. A typical receipt might look like this one, including such commonplace Swedish necessities as glass cookies and Giant Cactus. I think "moms" means "tax"--especially since my mom used to playfully exact food tax in the form of a bit of whatever ice cream treat we had used her money to purchase at the pool. I miss summer. (You too, Mom!)

whatever ice cream treat we had used her money to purchase at the pool. I miss summer. (You too, Mom!) but just a little bit ago we suddenly had no beam, and after calling the techinician discovered that the cooling water for one of the synchrotron's power supplies. It eats a lot of power to get electrons coursing around near the speed of light, even if they ARE lightweight. This means no more new data until after the day shift begins and they can fix the problem. We spent the rest of the night processing the data accumulated thus far, coding procedures for more advanced analysis, ... and taking turns in the massage chair.

but just a little bit ago we suddenly had no beam, and after calling the techinician discovered that the cooling water for one of the synchrotron's power supplies. It eats a lot of power to get electrons coursing around near the speed of light, even if they ARE lightweight. This means no more new data until after the day shift begins and they can fix the problem. We spent the rest of the night processing the data accumulated thus far, coding procedures for more advanced analysis, ... and taking turns in the massage chair. From the directions to the massage chair: "Drick ett glas vatten efter massagen. " Evidently Swedish massages have a dehydrating effect. There's so much Science to learn!

From the directions to the massage chair: "Drick ett glas vatten efter massagen. " Evidently Swedish massages have a dehydrating effect. There's so much Science to learn!

The spectra were looking good, and all through the house, not another soul was to be found.

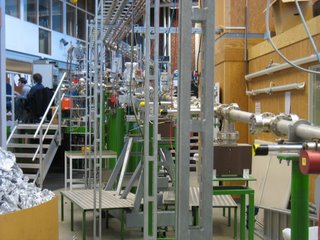

The spectra were looking good, and all through the house, not another soul was to be found.  We do all our work in an aluminum tree fort at one end of a long metal pipe branch. The operation of the

We do all our work in an aluminum tree fort at one end of a long metal pipe branch. The operation of the

), there are also some large-scale pieces of what can only be called art. Here Tim gives us a sense of scale for the ode to sailing. I think the title of the piece is translates "Ominous Ebony Wave of Death". My Swedish is rusty, though--meaning nonexistent. We went back to work and dawn found Tim and I sharing a beer.

), there are also some large-scale pieces of what can only be called art. Here Tim gives us a sense of scale for the ode to sailing. I think the title of the piece is translates "Ominous Ebony Wave of Death". My Swedish is rusty, though--meaning nonexistent. We went back to work and dawn found Tim and I sharing a beer.

Besides which this shot from my window is taken at ~1:30 am on the foggiest day thus far.

Besides which this shot from my window is taken at ~1:30 am on the foggiest day thus far. Danish trains are models of efficiency-- and they are also model trains. They seem to be made

Danish trains are models of efficiency-- and they are also model trains. They seem to be made  by Ikea, in fact. It doesn't amuse Tim (half of Tim appears in the shot of the train doors) after our redeye flights.

by Ikea, in fact. It doesn't amuse Tim (half of Tim appears in the shot of the train doors) after our redeye flights. sense of decency and socialism; a private bathroom; more storage space than my entire three-bedroom apartment back home; and hotel wall art which isn't bland and inoffensive.

sense of decency and socialism; a private bathroom; more storage space than my entire three-bedroom apartment back home; and hotel wall art which isn't bland and inoffensive.